Blog

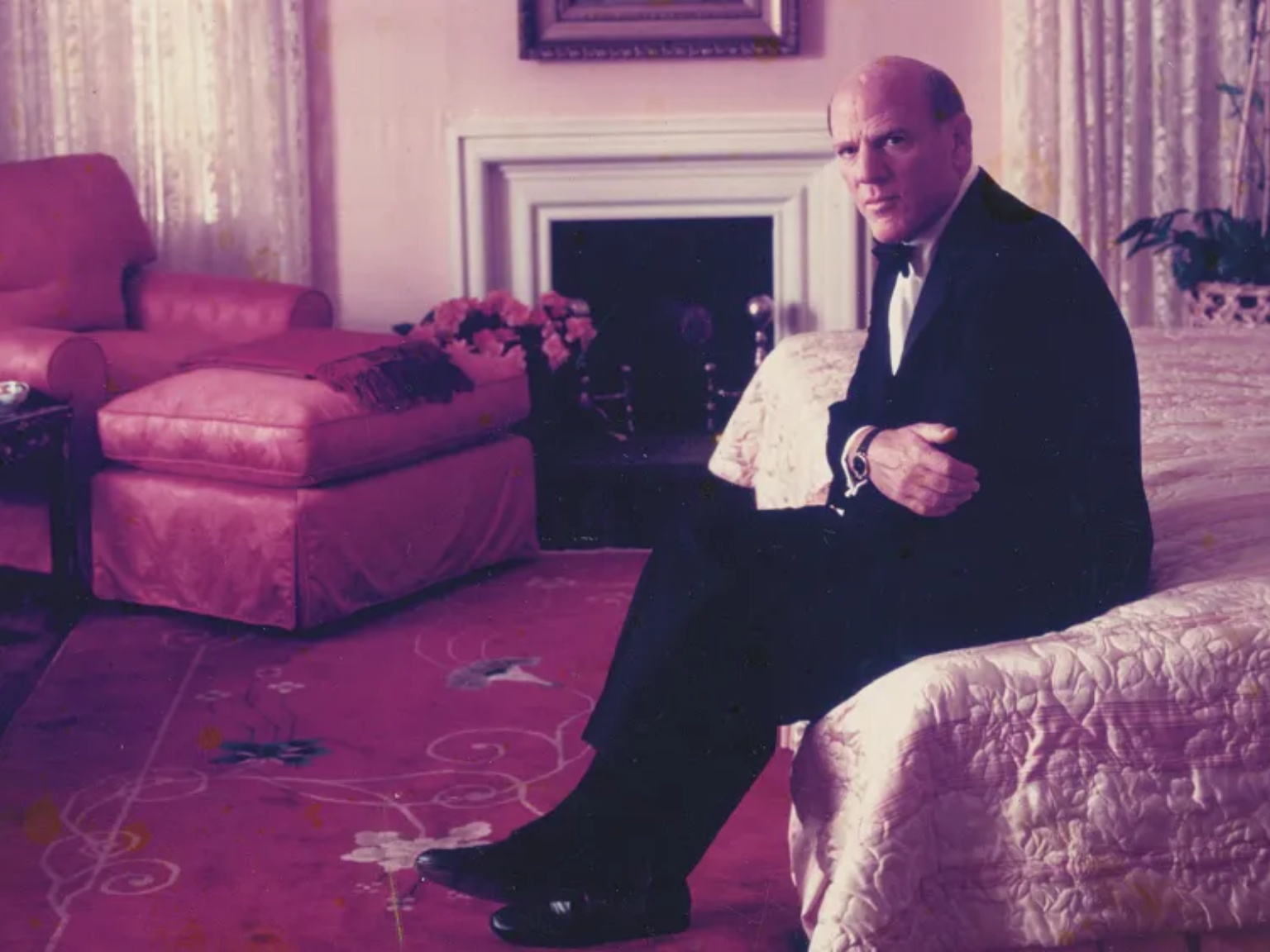

Diller Speaks: Hollywood’s Most Fearsome Legend Bares His Soul

Diller Speaks: Hollywood’s Most Fearsome Legend Bares His Soul

Barry Diller has one request before settling in on his living room sofa for a two-and-a-half-hour interview about the juicy revelations in his new tell-all memoir, Who Knew. “Don’t write about my house,” he says. “Don’t describe the decor.”

Consider it done. No mention here of the serene, unostentatious Beverly Hills mansion tucked behind a gate, the site of his annual Oscar party. Not a word about the furnishings, some of them chosen by his late friend Sandy Gallin — the manager to Michael Jackson and Dolly Parton and charter member of what Mike Ovitz once dickishly derided as the “velvet mafia.” Color schemes? Fabric choices? Forget it. This is a safe space.

Everything else, though, is fair game. Diller’s marriage to Diane von Furstenberg. His romantic entanglements with men over the years. His close alliances and bitter battles with Hollywood legends from David Geffen and Katharine Hepburn to Marvin Davis and Rupert Murdoch. And his bracing assessment of the current state of the entertainment industry — which he believes is being dismantled by a generation of “dictatorial” tech bros who, as he puts it, “have never actually made anything.”

Diller’s impact on Hollywood is so vast and enduring it’s sometimes easy to take for granted. As a young exec at ABC during the 1970s, he invented the Movie of the Week, giving a greenlight to a then-unknown Steven Spielberg for Duel, the director’s very first feature-length film. By 37, Diller was chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures, where he greenlit Beverly Hills Cop, Flashdance, Terms of Endearment, Saturday Night Fever and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Ten years later, he was launching the Fox network with The Simpsons, Married … With Children and 21 Jump Street, single-handedly creating a rival to the top three networks in just a few short years.

As for his private life, it’s long been the subject of whispers and blind items — especially in the Page Six era, when rumors swirled about “close mentorships” with a parade of young, handsome men (including, at one point, Johnny Carson’s stepson). Diller, in the past, has always let the gossip float where it may. But today, at 83, with his memoir just hitting bookstores, he’s cracking open the door more than usual. Indeed, the only secrets he’s apparently keeping these days are his decorating choices.

You’ve produced movies, television shows, Broadway musicals, built tech companies, run networks — and now you’ve written a memoir. Why now?

Honestly, I still don’t entirely know. I didn’t set out thinking, “I must publish this.” For a while, I figured maybe it wouldn’t ever see the light of day. I’d written most of it, and part of me thought, “Well, maybe after I’m dead someone will publish it.” But then I realized — then it won’t really be me publishing it, will it?

You’ve spent your life zealously guarding your privacy, so it was surprising to suddenly see you being so candid. Was there a sense that, as personal as the book is, it also had to be kind of impersonal — like you were telling your story without quite becoming the story?

It’s the first time I’ve ever been “the product,” instead of just working on one. And, yes, that felt really daunting and scary to me. I’ve spent my whole life crafting narratives for other people — movies, shows, companies. But this? Writing my own? That was a different kind of exposure. But the truth is, I just thought it was a good story. Not a how-to business memoir, not a legacy statement. Just a good tale — if I could tell it right and tell it true. And I know something about telling good stories.

How does one begin to catalogue a whole life? Did you keep journals?

No, I had no journals, no diaries. But I had a public, well-documented life. Which helped. And decades of calendars — dense, sprawling, sometimes maddening calendars. I rarely even looked at them. Mostly, I just sat down and vomited it all onto the page. That was Tina Brown’s advice, actually. “Just vomit it out, then go back and write.” I can’t remember if it was Tina or someone else who told me, “You don’t revise, you reveal.” Which is bullshit, of course, but charming bullshit. Still, it gave me permission to keep going.

And once you did start writing?

I found I remembered far more than I expected to. Once I started writing, whole scenes and details just unspooled. I’m sure I didn’t invent anything — I don’t think I’m capable of that kind of fiction. But there’s something strange about memory. Ask me what I remember, and I’d say, “Nothing.” But start writing, and boom, it all comes flooding back, for better or for worse.

Your book captures a version of Hollywood that’s almost mythic now. You write about these operatic, over-the-top characters — Robert Evans, Marvin Davis — who make their modern equivalents seem anemic. Do you feel nostalgic for that time?

It certainly was a time of more flamboyance. The business required big personalities, extremes, people who operated without restraint. That used to be the fun — and the engine — of the entertainment business. Now it’s different. Everyone is more cautious and conformist now. Worried about being canceled or sued. The rough edges have been sanded off. We’ve gone from a town to a spreadsheet. And obviously that can’t help but impact the creative output as well.

You mean because Hollywood is now run by tech companies?

That’s part of it. Netflix, Amazon, Apple — they control the game now. But they don’t have any real roots in this community. They didn’t grow up yearning for Hollywood. They don’t care about its history, its mythology. Their interests are driven by entirely different models. Amazon doesn’t care if your movie is good — they care if it helps keep people subscribed to Prime and buying socks. Not exactly a recipe for greatness.

Do you think that true of Netflix as well?

Netflix won’t even tell you how many people watched your movie. Why? Because they don’t want you to know. Their business is entirely algorithmic. They care about satisfaction across a vast catalog. Your individual film? It’s just another tile in the grid. It’s no big deal if it succeeds or fails.

So how do you make something that lasts in this environment?

That’s the problem. Great work doesn’t sit in the culture anymore. It’s gone in a flash. One hand clapping in a forest. We used to have shows that 50 million people watched on the same night. Now? If something gets 7 million, it’s a smash hit. There’s just too much. Too many options, too much noise. And streaming — while miraculous in its own way — has fractured everything.

Is that why you got out of the movie business?

We stopped producing movies a couple of years ago. If I were starting out today, I don’t think I’d do it. It’s not just about the breadth of the audience, it’s about the sense that you were part of something. That your work had cultural gravity. That’s hard to feel now. The community is gone.

Is it nostalgia? Or do you really believe the system was better then?

It’s not about better or worse. It’s about ethos. There used to be a kind of inbred, incestuous quality to Hollywood that was actually good. It breathed its own air. It had a small-town feeling. Now it’s just an outpost of the cloud.

What about the audience? Does it care anymore?

That’s the biggest loss. We used to make movies or TV shows and you could immediately feel the impact. People talked about it. It lingered. A hit movie could live on for a whole summer. Now things drop on a streaming service, maybe trend for a weekend, then disappear. Nothing lasts.

Are you still watching new stuff?

Of course. I consume a lot. I liked the first few episodes of Your Friends and Neighbors with Jon Hamm, then it sort of fell apart. I’m watching MobLand now — Helen Mirren is fantastic, and even Pierce Brosnan, whom I never thought much of, is great in it. But mostly, I feel like I’ve seen everything before. It’s hard to surprise me. But I’m 83!

You left Hollywood when it was still riding high. These days a lot of people seem to be writing it off. Do you share in that pessimism?

I don’t think Hollywood studios will go out of existence. But I think they’ll be much smaller operations than they have been in the past. Their days of dominating media have passed, and Hollywood will never recover from that. Hollywood is now under the dictatorial realm of the technology companies, so they are a smaller piece of the pie.

You’ve been pretty critical of the tech overlords’ impact on Hollywood. What don’t they get about entertainment?

They’re just different. Their brains are trained differently. Tech is binary. Ones and zeros. You have these gigantic companies controlling the culture now where the person at the top has never actually made anything. It’s astonishing. They’re overseeing entertainment without ever having touched it. It’s a system designed for predictability and efficiency — which is the exact opposite of creative work. That’s the tension. Now, someone like Steve Jobs — he was also an artist. An Edison. But those kind of people are rare. I actually think Bezos is closer to Jobs than most people give him credit for. He’s got enormous wisdom. But most of the others are pretty flat.

What about Musk?

Musk is will. Pure, brute will. A willful machine. I admire what he’s achieved, but it’s execution, not imagination. He can build the car, sure. But that’s not artistry.

You mention in the book that you never use data or research to guide your creative decisions. Why is that?

Because data can’t predict anything meaningful in creative work. It can’t tell you if something’s a good idea or a bad one. It can’t tell you if a performance is brilliant or flat. You know, back in the day we had all those dial-test screenings — people turning a knob when they liked something or didn’t. Utter nonsense. Garbage in, garbage out. You have to trust your gut. That’s the only thing that works. Most people are so insecure about keeping their jobs that they need data to justify their every decision. It’s like, don’t blame me, blame the data! I prefer to go with my gut.

Has your gut ever steered you wrong?

Oh, endlessly. Of course! I’ve backed plenty of turkeys. But the process is still better than anything else I know. It’s how I’ve always made decisions — whether it’s a show, a movie or even an ad campaign. I remember recently we were casting a voice for a new Hotels.com campaign. We tested four options, and the worst, whiniest voice tested highest. I said, “Nope. We’re going with the one that actually sounds right.” And we did. Because your ear knows better than a damn focus group.

You write in the book about keeping your instincts “clean.” What does that mean?

It means resisting cynicism. Cynicism corrodes instinct. The older you get, the more it creeps in. You start thinking you know too much, that you’ve seen it all before. You lose your naïveté — and that’s a killer. I’ve always tried to hold on to mine — maybe way past the expiration date. But it’s what keeps your instincts sharp.

You also say you have never been motivated by money — which is a pretty surprising claim from a billionaire.

My parents were well off, so unlike most people, I didn’t grow up worrying about money. It was never a motivating factor for me. I’ve never made a single decision based on it. And once you have a certain amount — unless you have truly grotesque tastes — what else do you need? People ask, “Why keep going after the first billion?” It’s not about that. For me, all I ever wanted was to matter.

To be seen?

Exactly. To be part of something, to leave a mark. That’s what drives most people in this business, whether they admit it or not.

At one point, you made a bid to buy Shari Redstone‘s company. What would you have done with Paramount had you succeeded?

Well, it would have been a big pain in the ass! As I’ve said, I bid on it more out of duty than desire. Duty in the sense that Paramount had been two big chapters of my life. And this would have been the third chapter. So it would have been a kind of closing of a circle. Also, I believed that if I did get control of it, I knew what needed to be done. I can’t articulate what that is — because that would be inappropriate. Part of it, though, would’ve been leadership. I’ve always believed hiring an outside CEO is basically an admission of failure. Ideally, you grow people inside the company — people who marinate in its culture. You can interview someone for a hundred hours and still not know how they’ll function in your world. But when the sale became an auction, I said, “I’m not going to win against someone with a vastly better balance sheet.” And I thought, “Do you really want to do this?” In the end, I said, “No, I really don’t.”

There’s a moment in the book where you mention how when you were running the company, a Paramount executive made gay jokes in front of you. That hit me — because it felt like even at the top, you still had to tolerate slights like that.

Yeah, I still remember that. That sort of casual cruelty. I wasn’t closeted — I just never declared. And yet the reaction to that New York Magazine excerpt was wild. Suddenly I’m “coming out.” At my age! Diane, my wife, and I laughed about it. It was absurd. The door was always open. If I was in a closet, it was made of glass and full of light.

Obviously, the reaction to your book shows that some people are not buying that. But the pain of growing up when you couldn’t be open about it — that’s real. And you write about that with a lot of grace.

Thank you. People can say what they want. I didn’t want to live a hypocritical life. That was the main thing. So I just lived as I lived. But yes, of course it left a mark. Any minority experience does. That’s universal.

You mention in the book that you wish you had been public about it earlier.

I do wish that I had made a declaration. Maybe that would have helped people. But I never lied. I never pretended anything. I never hid. People in my circle knew about my life with both men and with Diane. The only thing I didn’t do was make a declaration. I chose not to for a lot of complicated reasons.

Would life have been different for you if you had made that declaration earlier?

Maybe. Maybe not. But I was never hiding. I didn’t issue a press release either. And yes, there were moments, especially early in my career, when I was afraid of how people might react. But in practical terms, it didn’t hold me back.

Except maybe emotionally.

Yes. That part is true. The internal part — the shame, the concealment — that certainly leaves a mark. And that’s why I wrote about it.

What about the “Velvet Mafia” stuff? Did that ever exist?

Nonsense. That was a dumb straight-man fantasy — this idea of some powerful gay cabal running the business. We didn’t have anything in common except sexuality. It was projection. Pure and simple.

Overall, do you think things have changed for the better?

Oh, absolutely. There’s still progress to be made, but the idea of “coming out” in the old sense — it’s mostly obsolete now. Young people may still struggle, but we’ve come so far. And that momentum can’t be stopped, no matter who’s in office.

I know that you had a distant relationship with your parents and particularly with your brother, who suffered from his own demons. Was there ever a moment when your family acknowledged your success?

No, certainly not my brother, who died years ago. And with my parents, the relationship was always very formal. Loving, yes, but not in any way that was rich with texture. But they enjoyed my success, I think, more than I did, though they never really told me that. I have never been very good at living in the moment. I always found it easier to live in the future or in the past.

You still own a lot of media, including People magazine and The Daily Beast. Are you optimistic about the future of that side of the business?

Actually, yes. Our print and digital publishing business is performing better than any of the big players — better than Condé Nast, better than Hearst. We’ve invested in our brands. We believe in them. AI is a threat to everything, of course, but a strong brand is still a defense. It’s not just defense — it can be offense, too.

The Daily Beast has been a bit of a money pit, though.

(Laughs.) Oh, for my sins, yes. I’ve poured stupid money into that thing, going back to the Tina Brown days. At one point, we lost $120 million. But I finally said, “Enough.” We were about to sell it — then Ben Sherwood and Joanna Coles came to me with a plan. I said, “OK, one last gasp.” And you know what? They turned it around. It’s now profitable. Shockingly.

We’ve seen AI really eat into the traffic and relevance of a lot of media brands in recent years. What kind of defense does the media have against that?

When we bought Meredith and inherited sites like About.com, we applied a very specific playbook. We reorganized those brands, made them efficient, invested in their identities. That’s what matters — identity. That’s our hedge against AI, which I do see as an existential threat.

And People? It’s had a bumpy ride in recent years.

It’s doing well now. But it was on the edge, no question. What we’re doing right is focusing on what makes the brand matter. We invest in that — its editorial quality, its visual identity, its authority. You can’t out-AI a robot. But you can stand for something human. That’s our strategy.

Beyond media, what are the parts of IAC that might surprise people?

Most people don’t realize that a huge chunk of our business is home services — Angi, Handy, that kind of thing. It’s not glamorous, but it works. It’s consistent. The boring stuff funds the riskier stuff.

You said that you’ve never been the product before. With this book, you, Barry Diller, are definitely the product. What’s it been like for you?

Appalling! (Laughs.) Honestly, I hated it. I’ve spent my whole life behind the curtain, shaping other people’s narratives. There’s a cost to never shaping your own. But I never wanted to be on the marquee. So doing press, talking about myself — it’s been excruciating. But I thought the story was worth telling. And I thought it might be useful to some people. I just didn’t want to write a “here’s how I made it” business book. That didn’t interest me. I wanted to tell a story.

What’s the biggest surprise that’s come from sharing that story?

The reaction to my so-called “coming out.” That people fixated on that, like it was some seismic revelation. That felt very strange to me. But I suppose people like clarity — and declarations. They want the label. And the media loves a headline.

You’ve spent your career making things happen — building empires, companies, brands. Day to day, what’s the impulse that keeps you going?

I like to work. It’s that simple. I like solving problems. I like building. Even when I’m not the youngest guy in the room anymore, that impulse hasn’t changed. But at a certain age, you stop thinking about conquest and start thinking about stewardship. Every day, I get up and ask, “What’s left to make better?”

At 83, do you think the best parts of your life are behind you?

Not at all. The best parts are always ahead if you keep moving. If you stay curious. If you resist cynicism. I still wake up with ideas. That’s enough.

So, retirement …?

Never, never, never. No, never!

What would you like to be the headline of your Times obituary?

Barry Diller is done. (Laughs.)

This story appeared in the May 21 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.